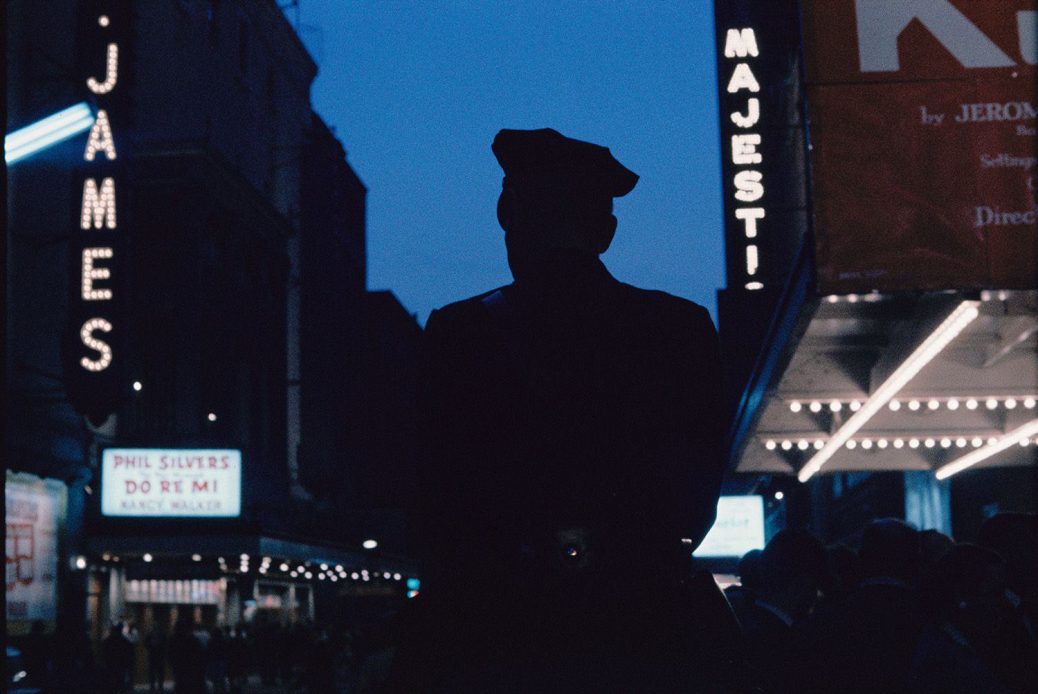

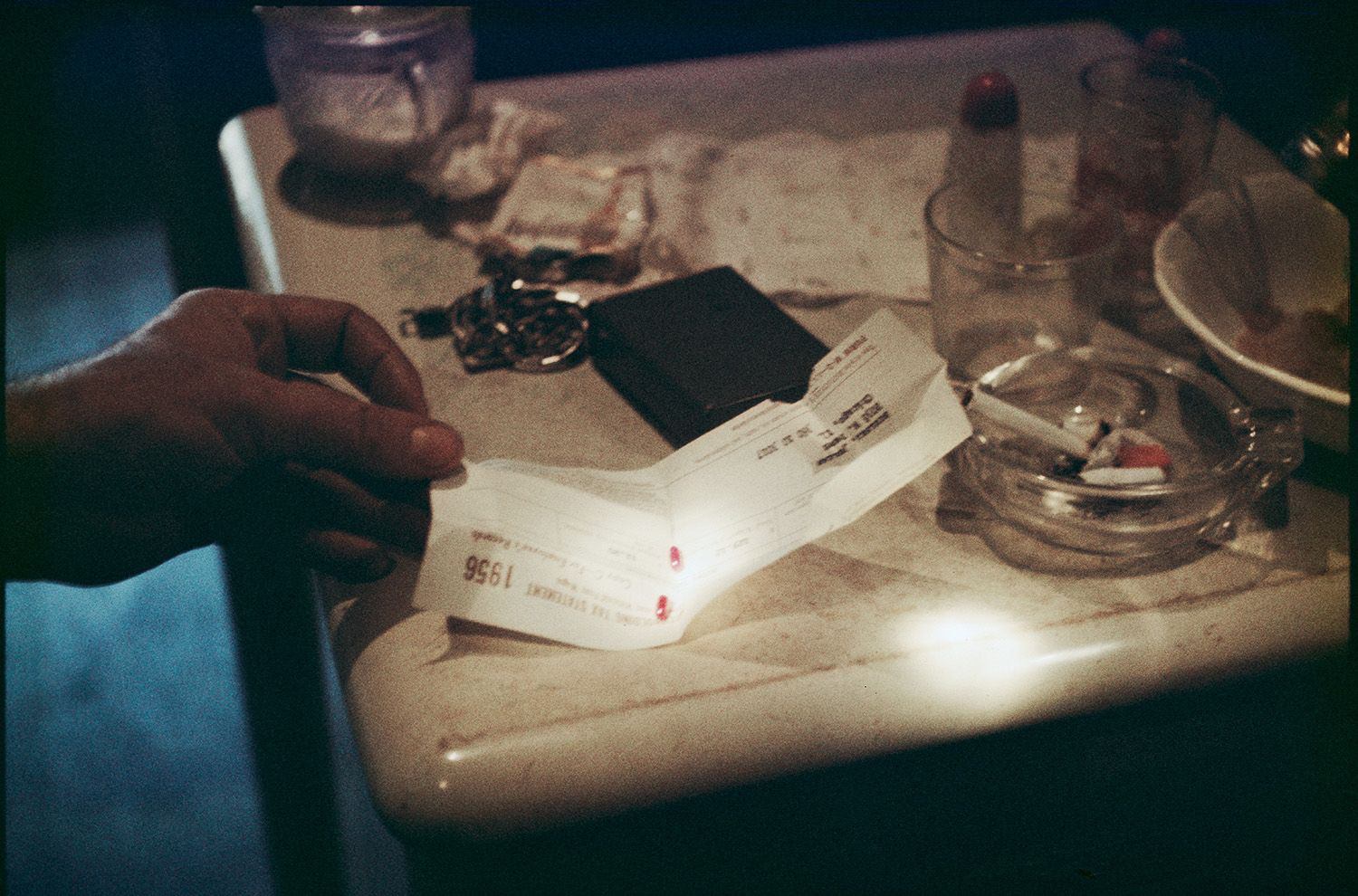

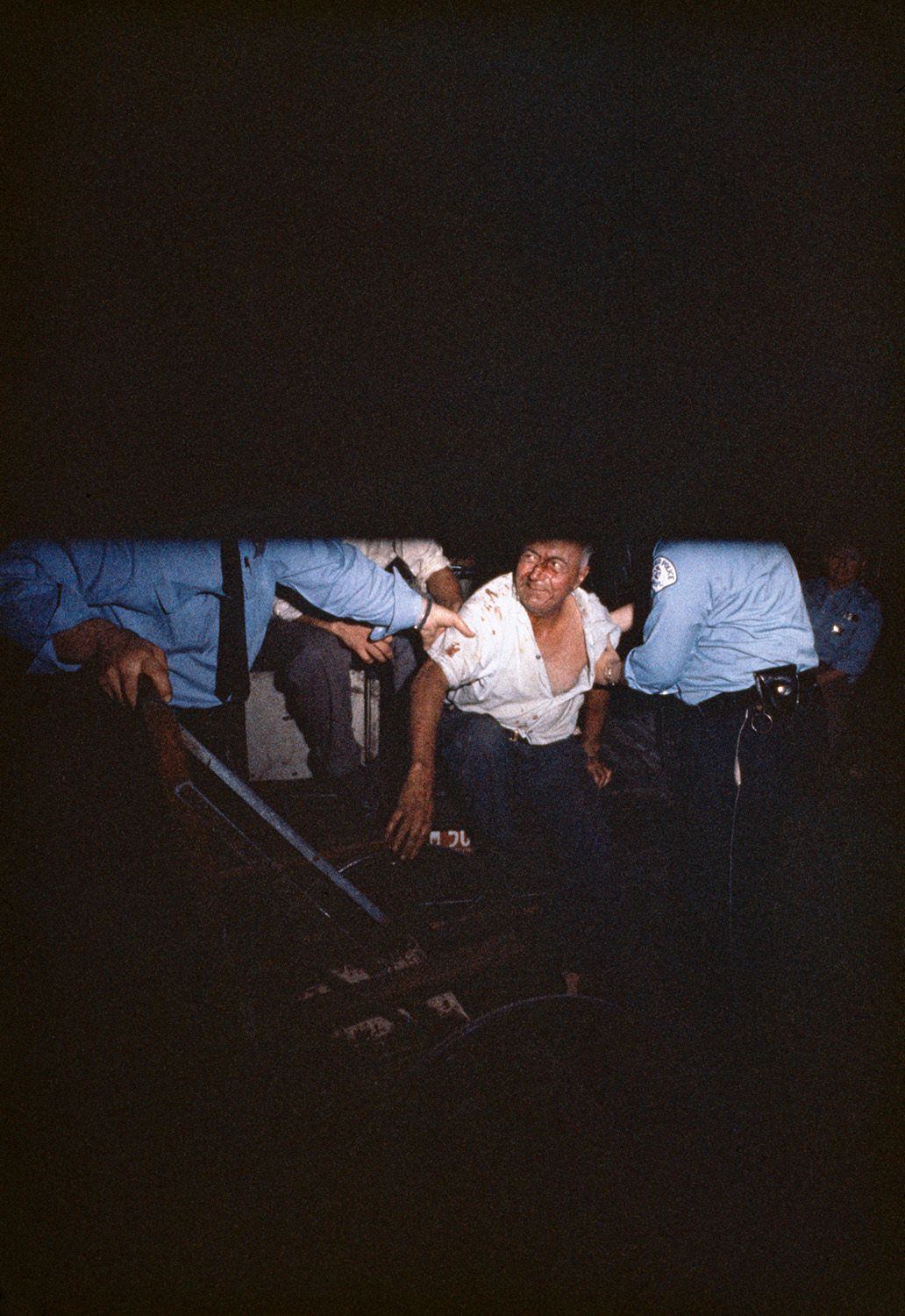

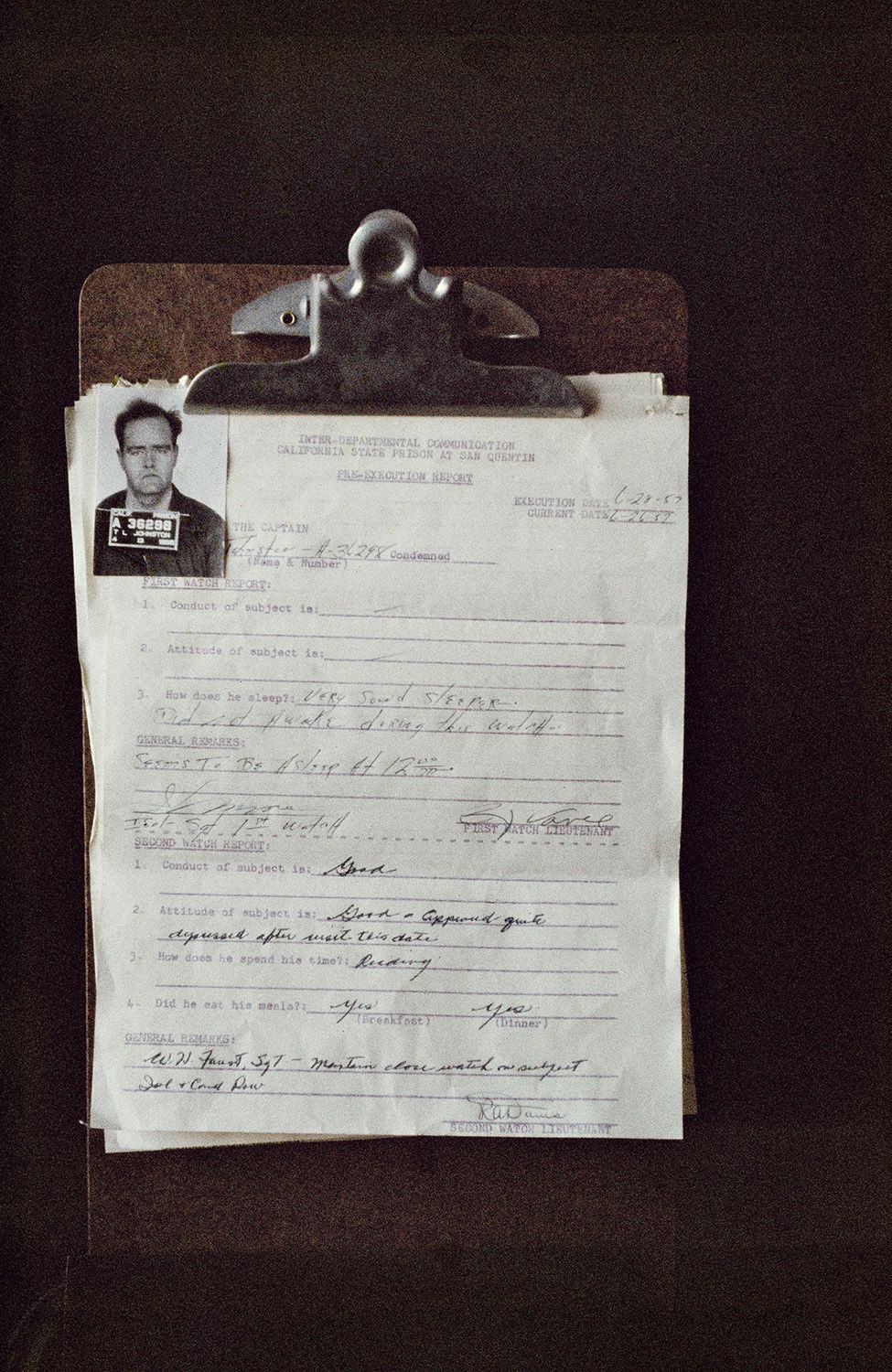

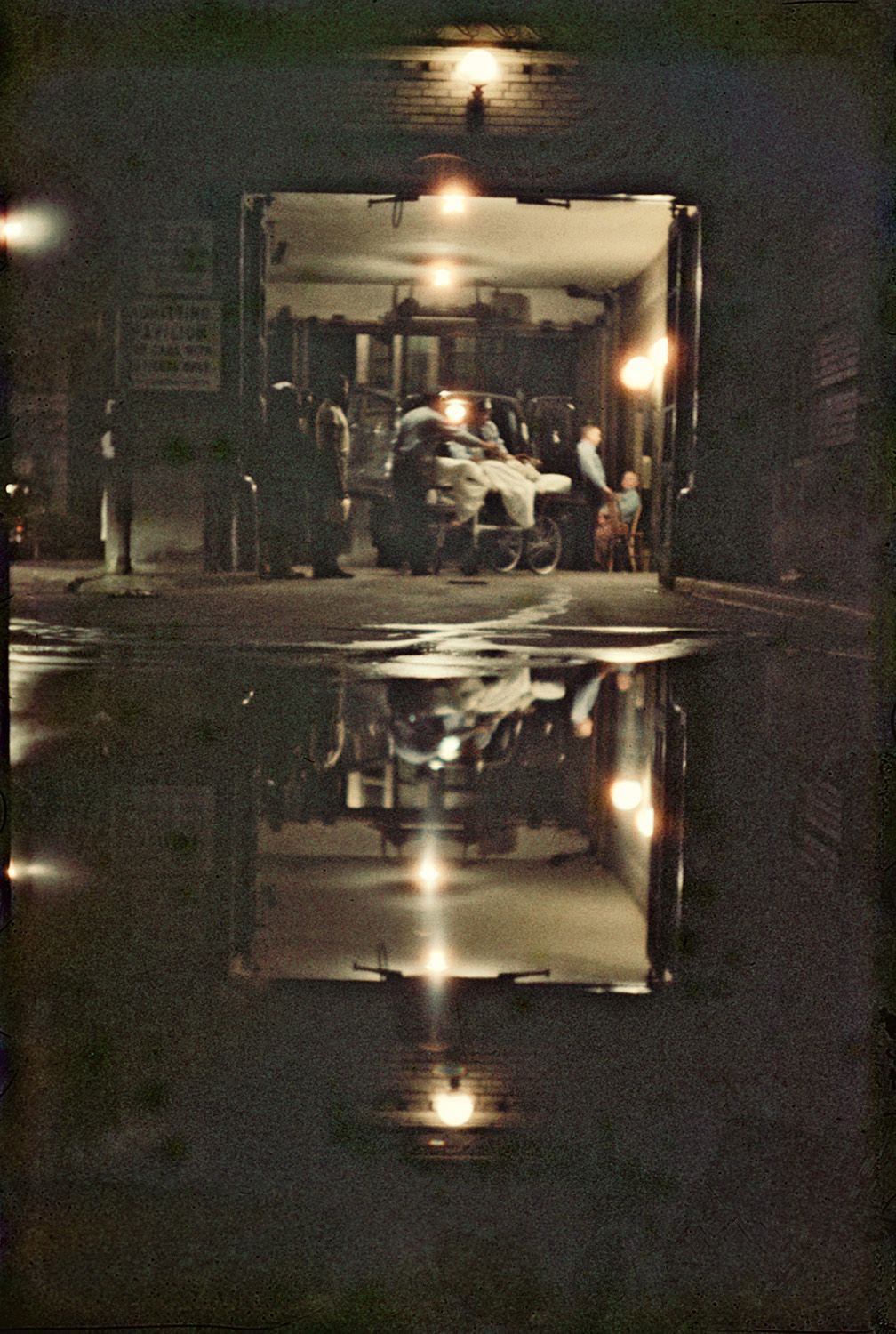

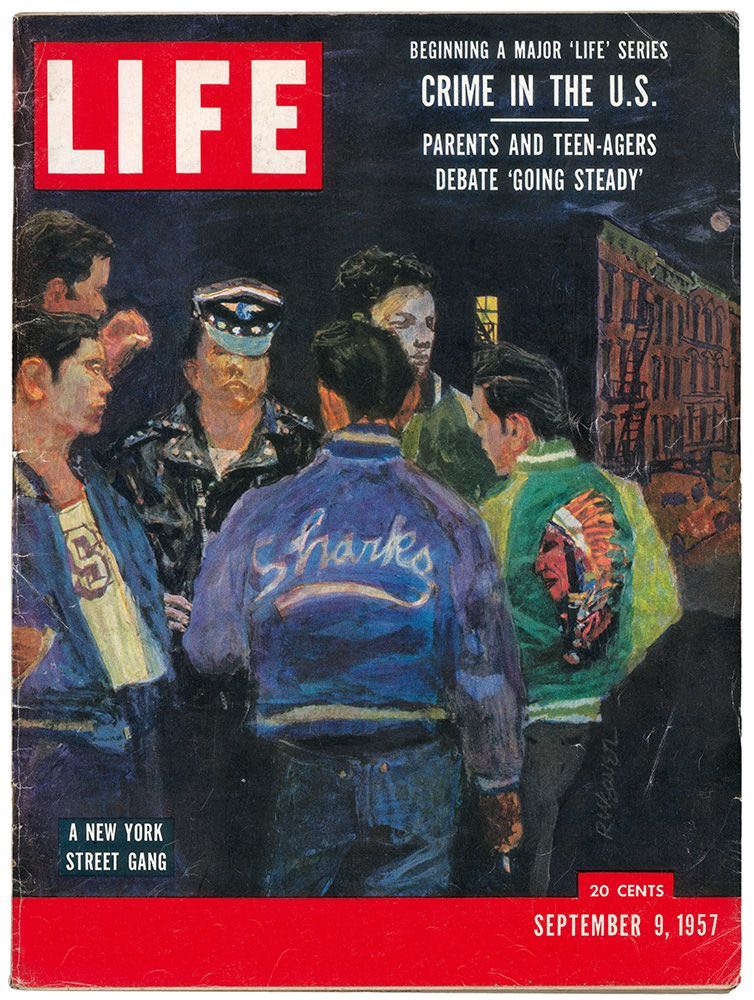

Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime 1957

Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime 1957

Gordon Parks’ ethically complex depictions of crime in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, with previously unseen photographs.

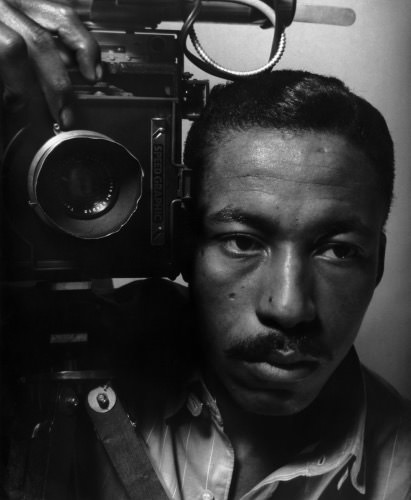

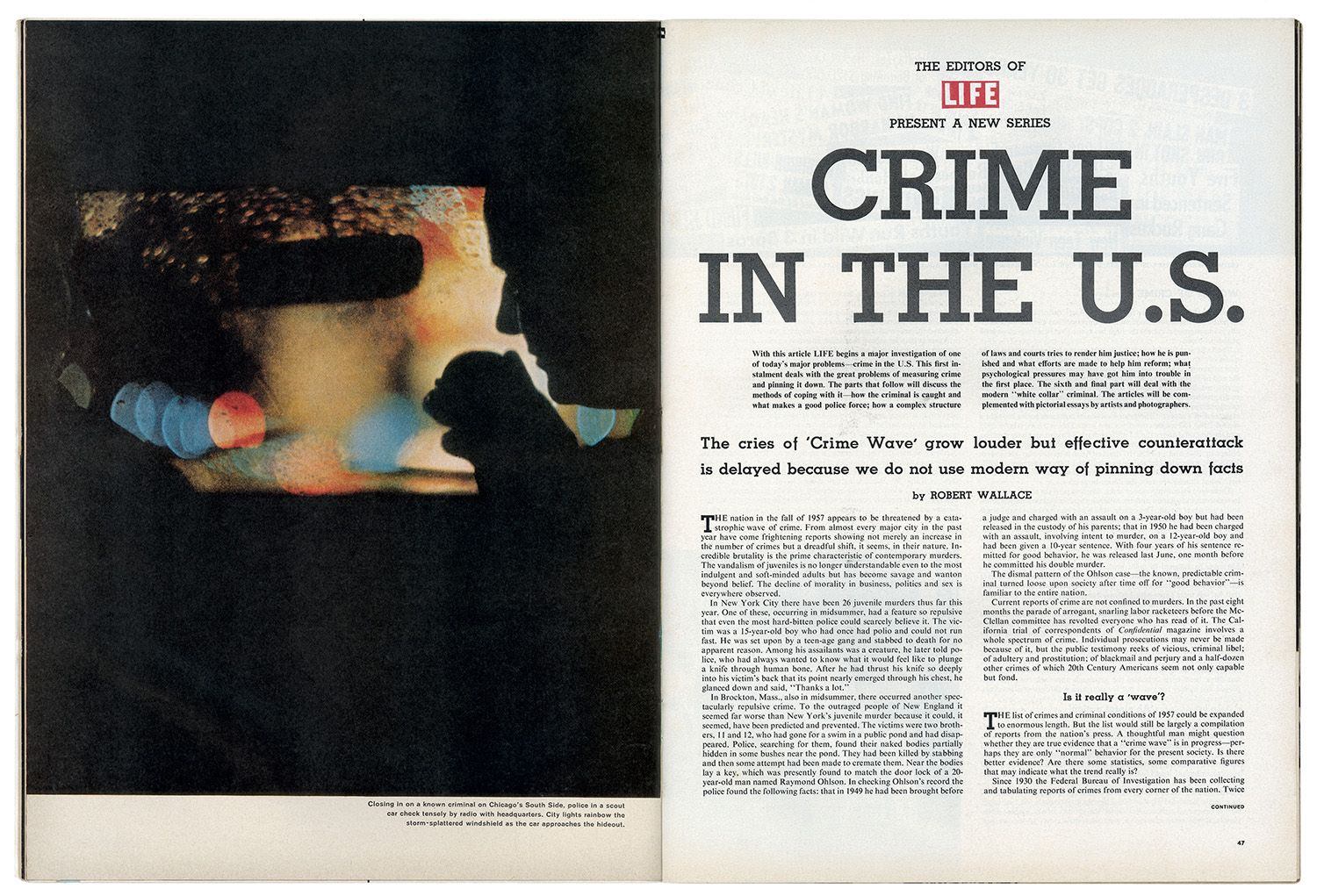

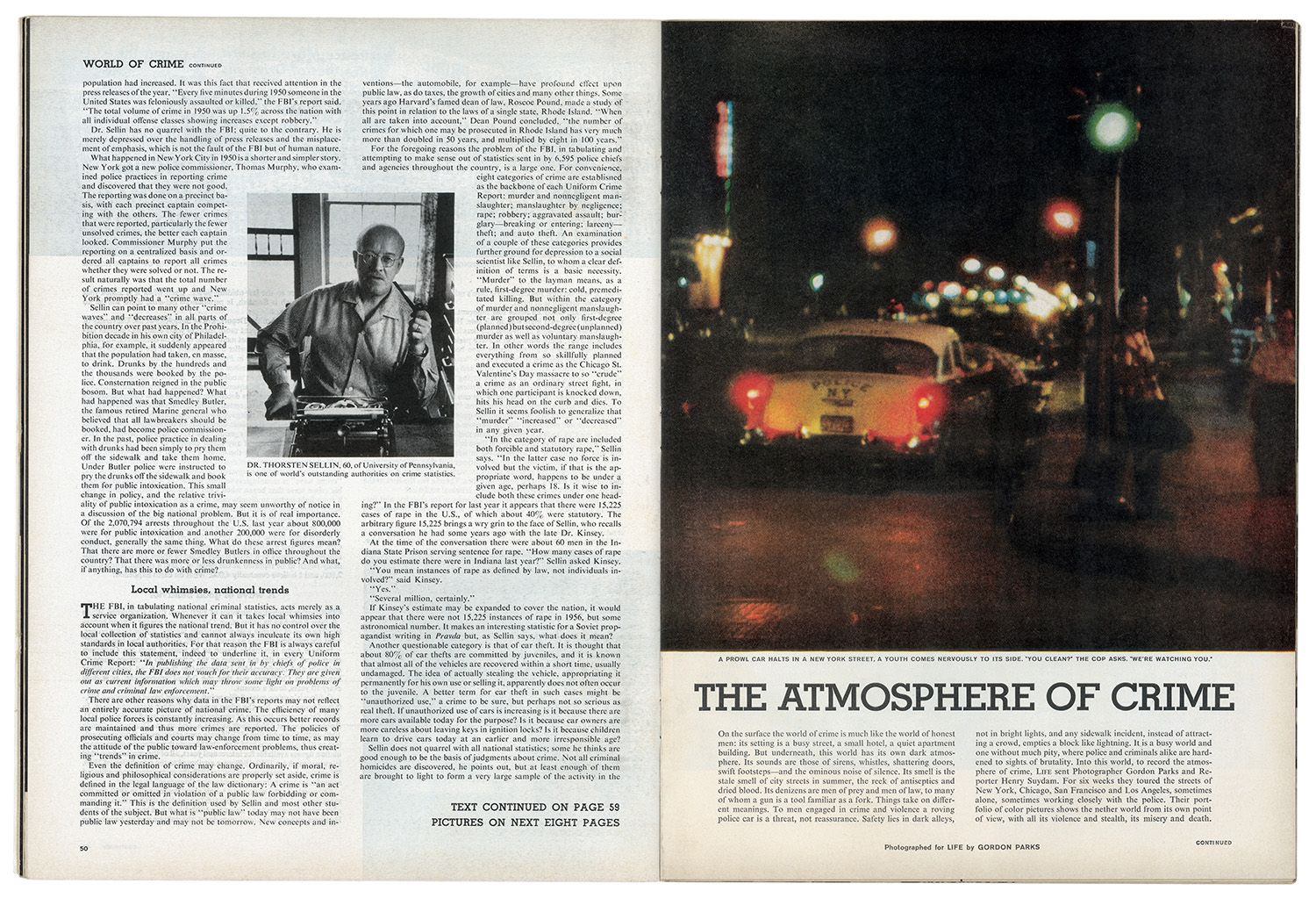

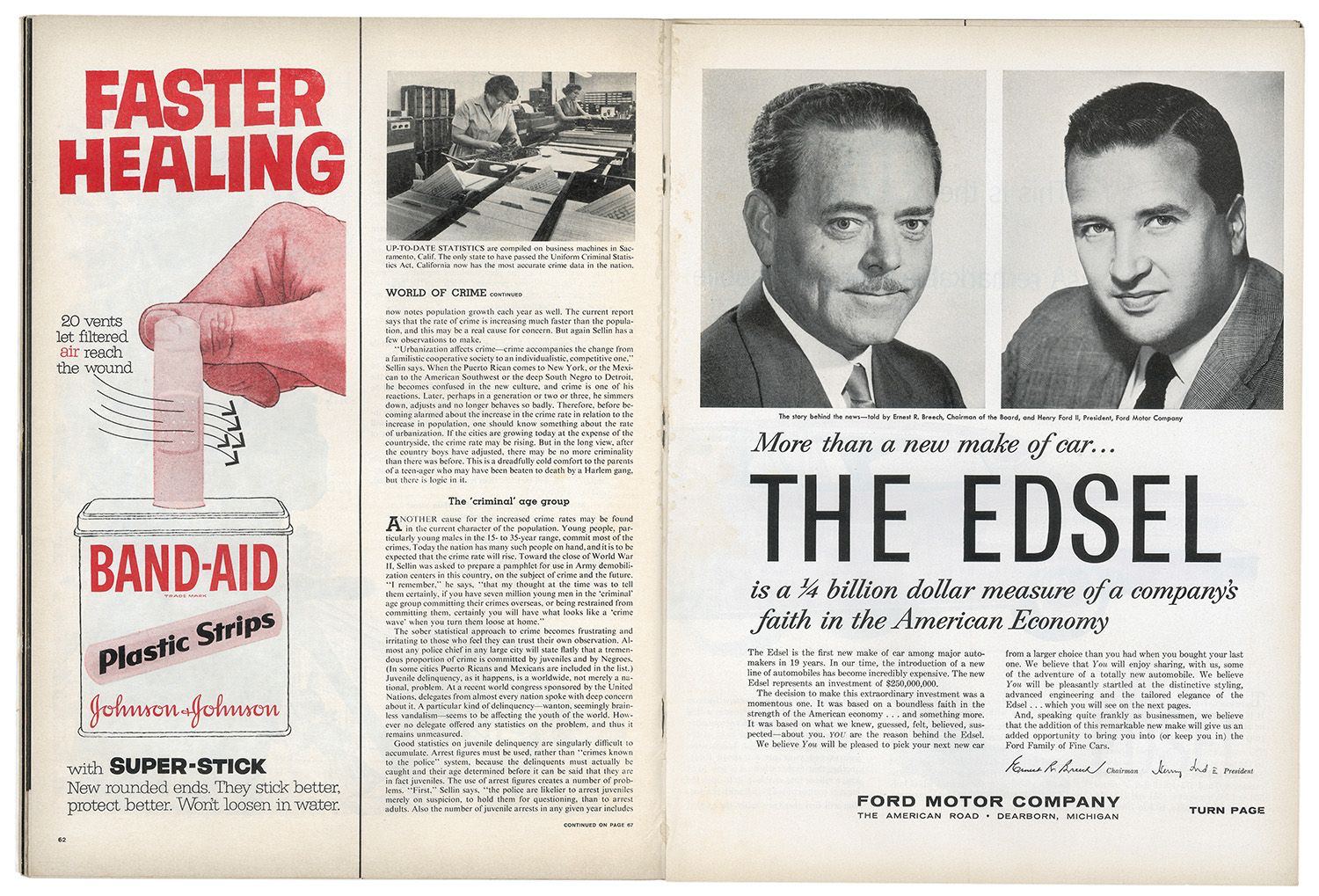

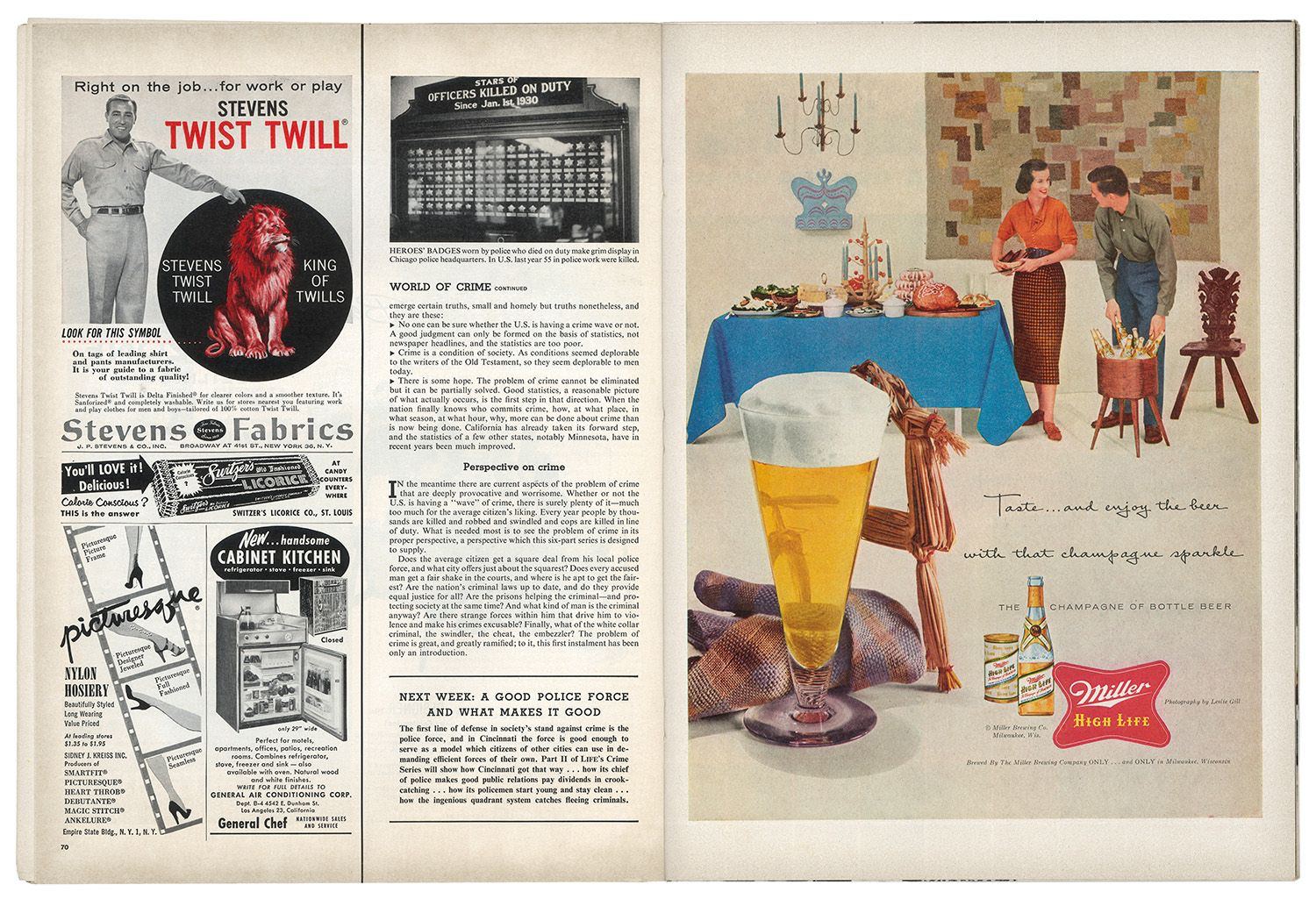

When Life magazine asked Gordon Parks to illustrate a recurring series of articles on crime in the United States in 1957, he had already been a staff photographer for nearly a decade, the first African American to hold this position. Parks embarked on a six-week journey that took him and a reporter to the streets of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

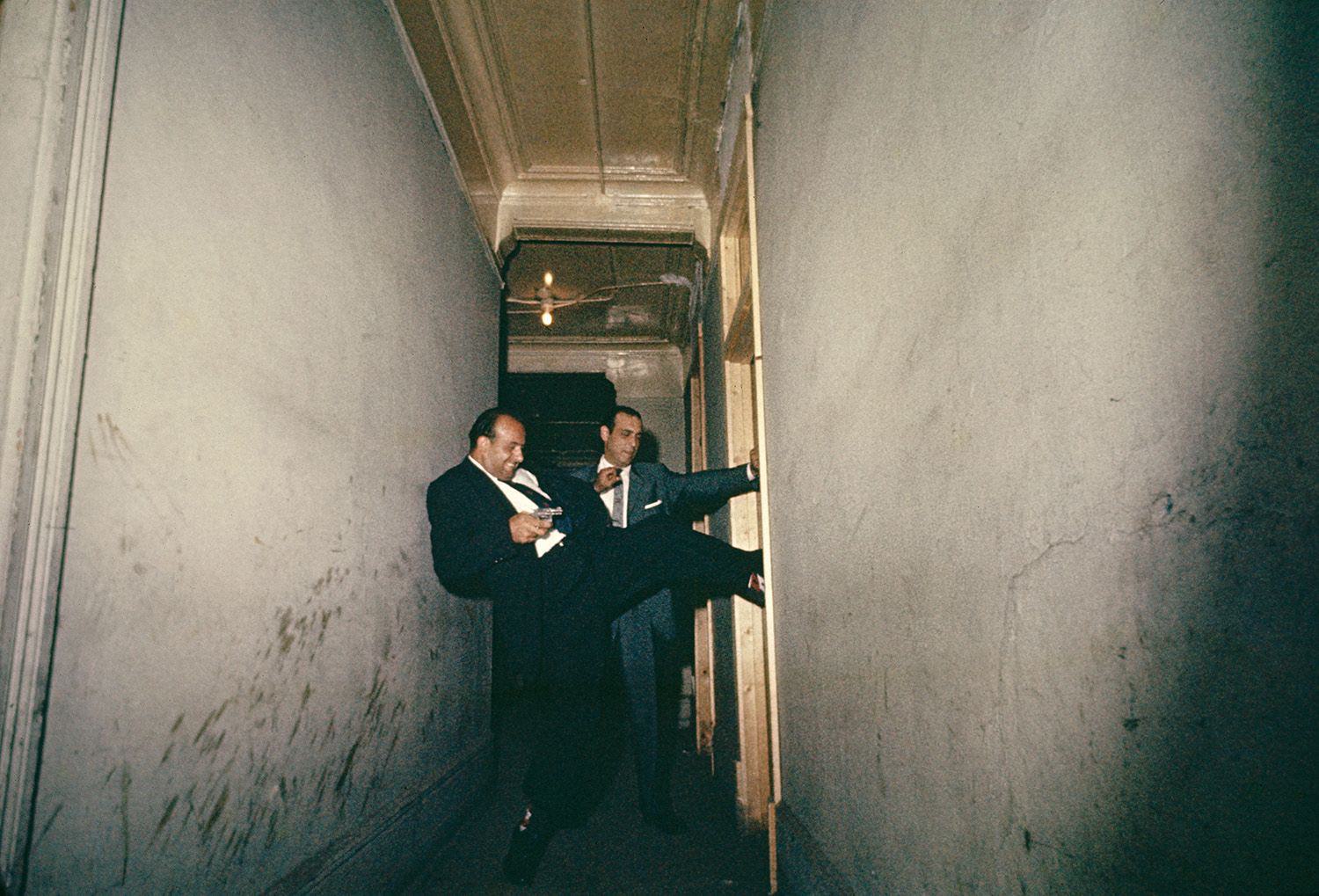

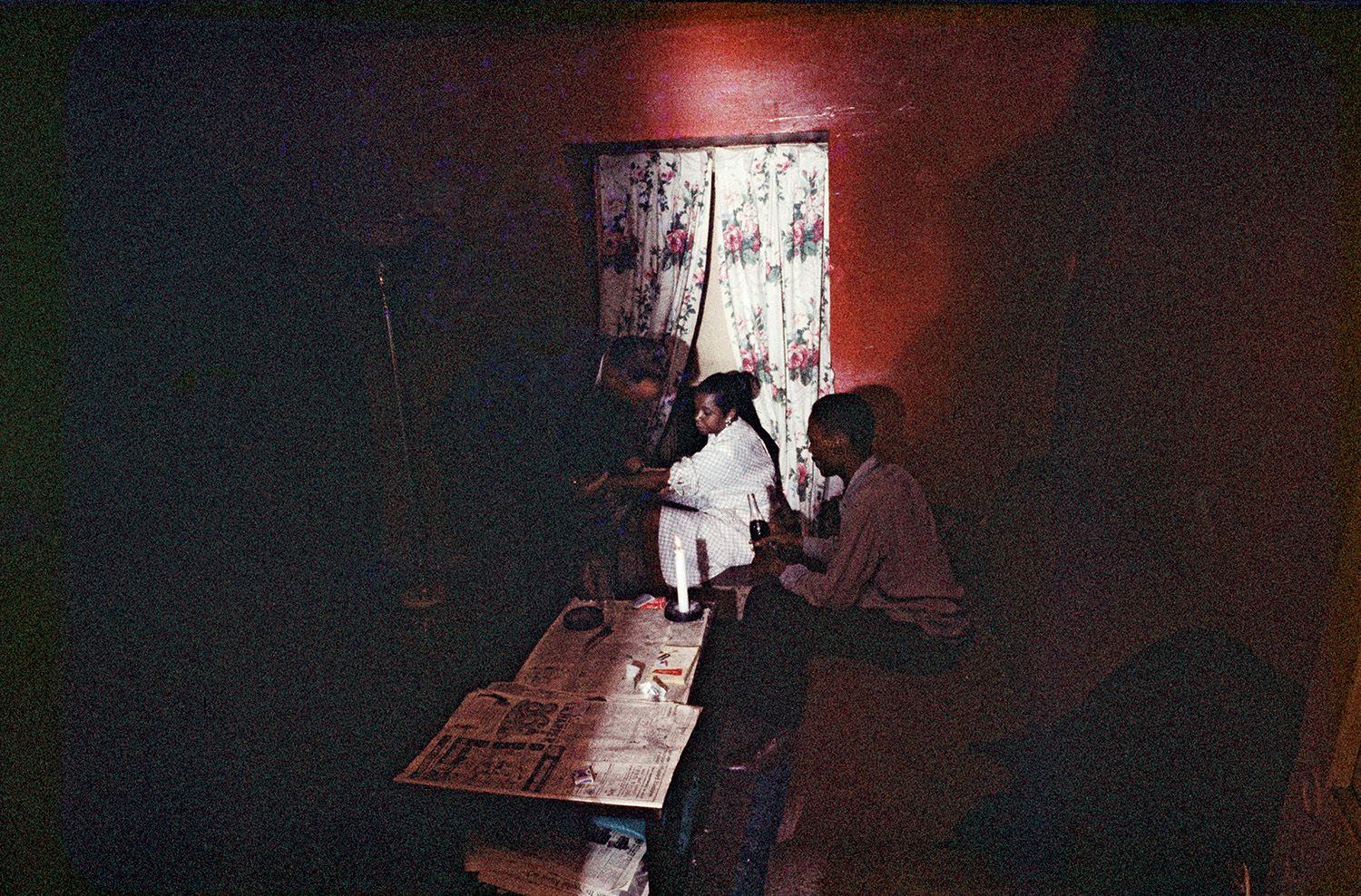

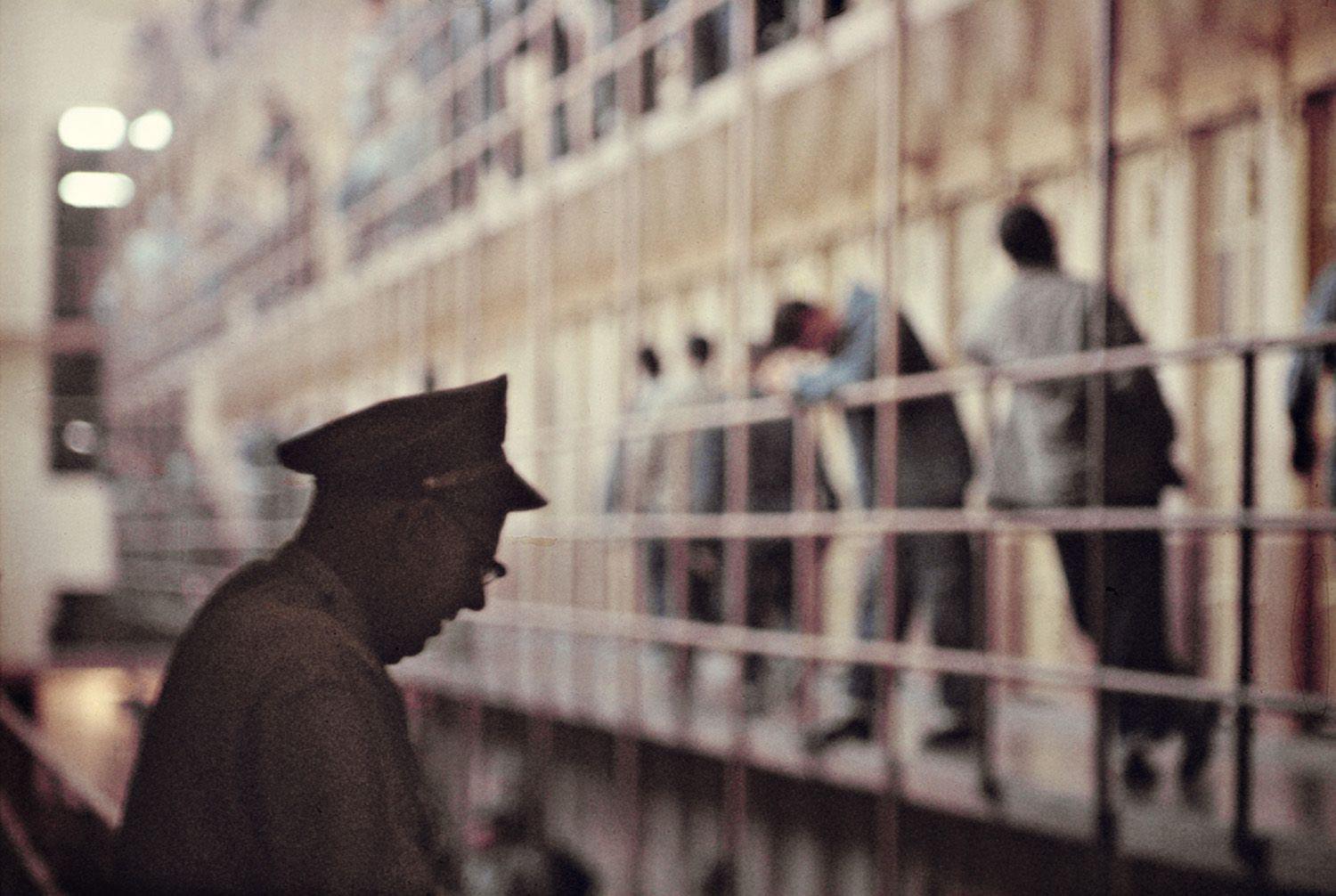

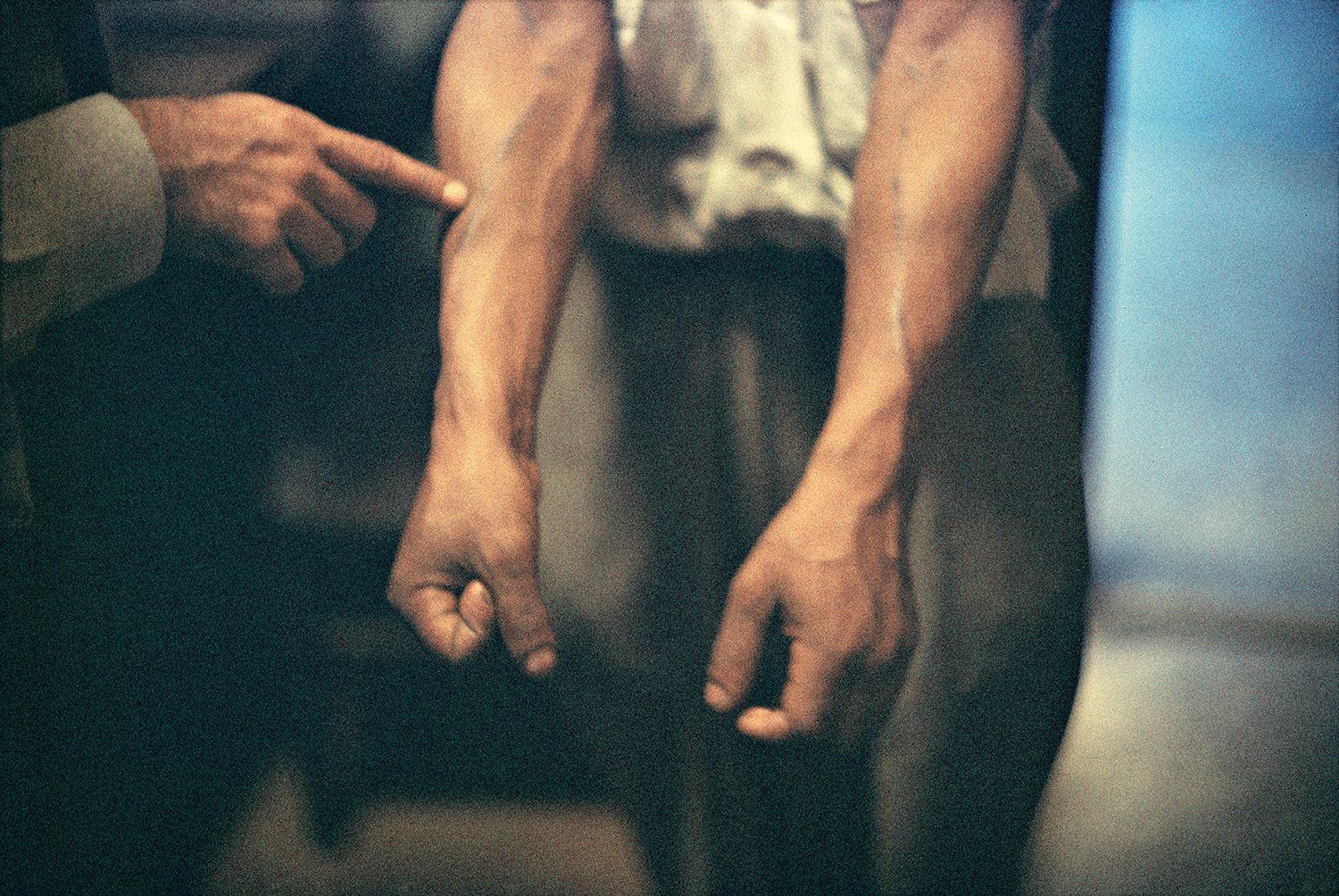

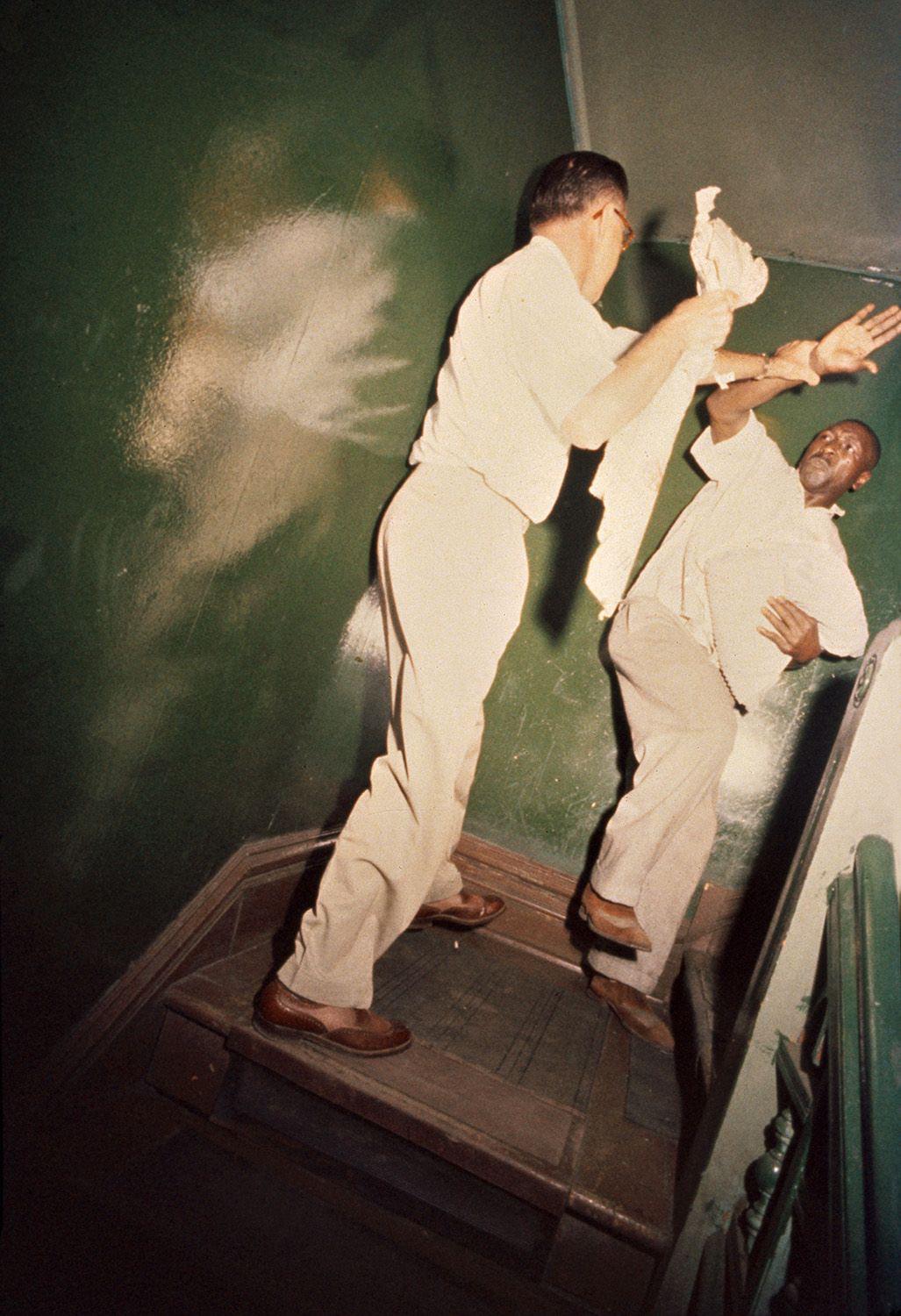

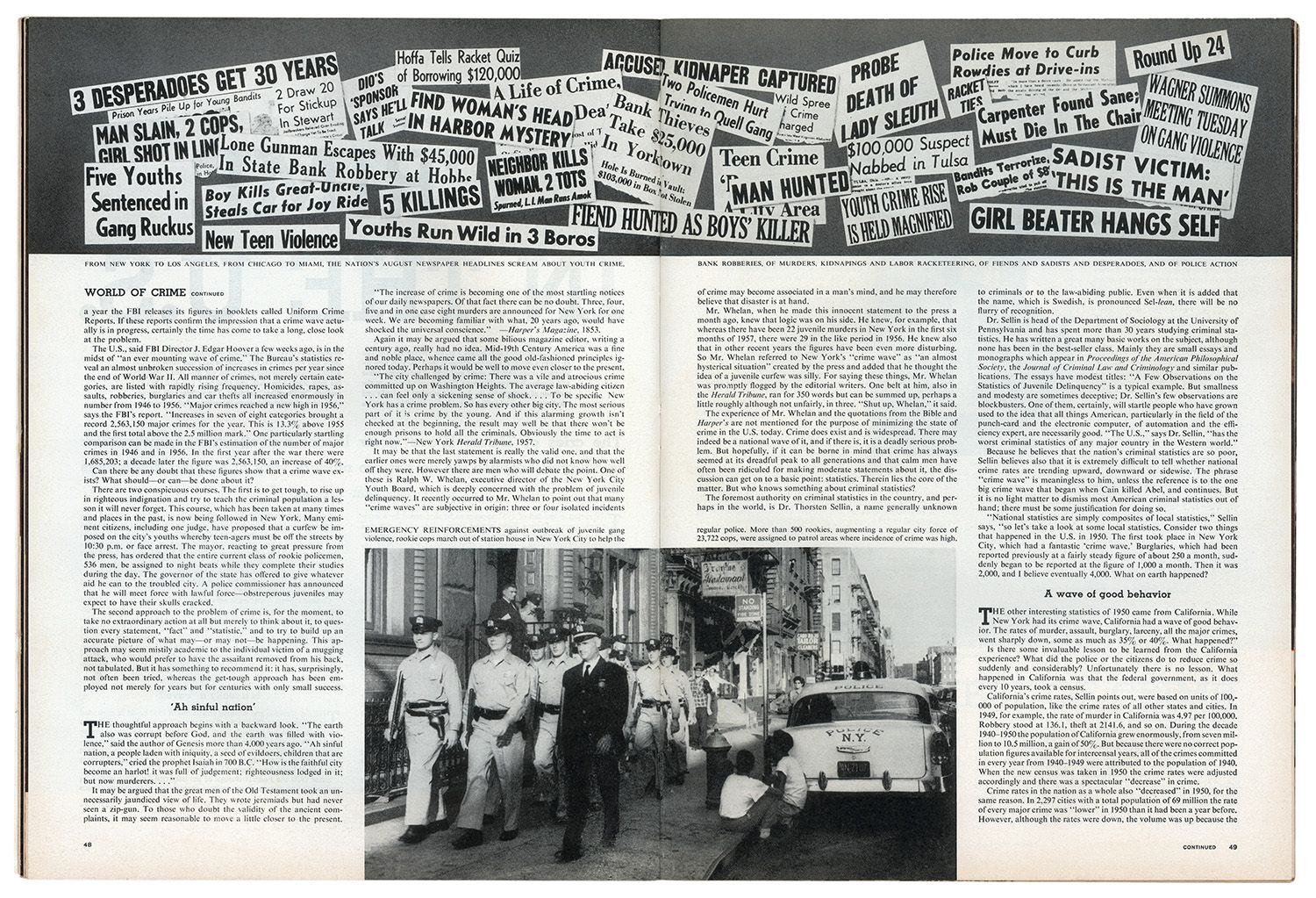

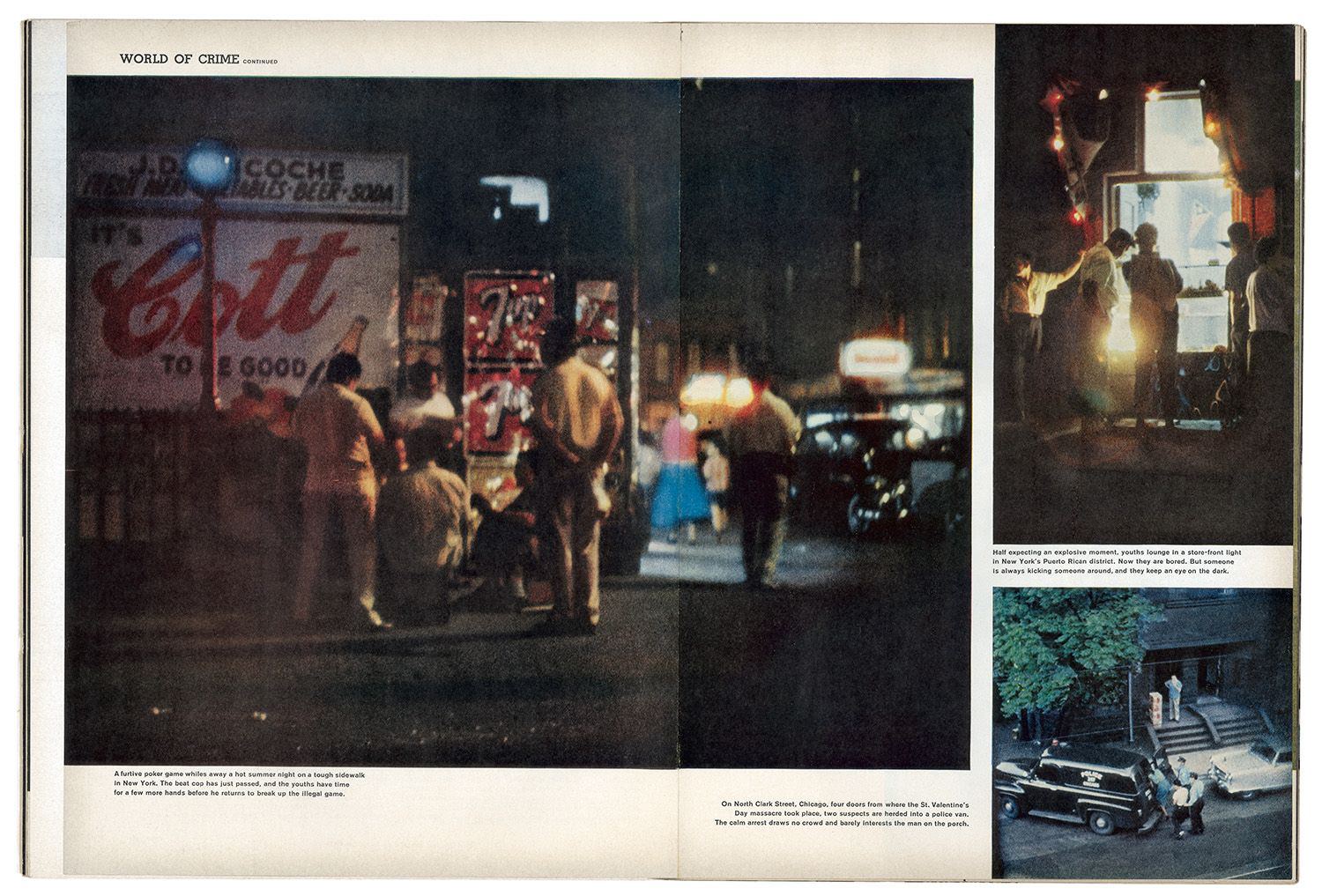

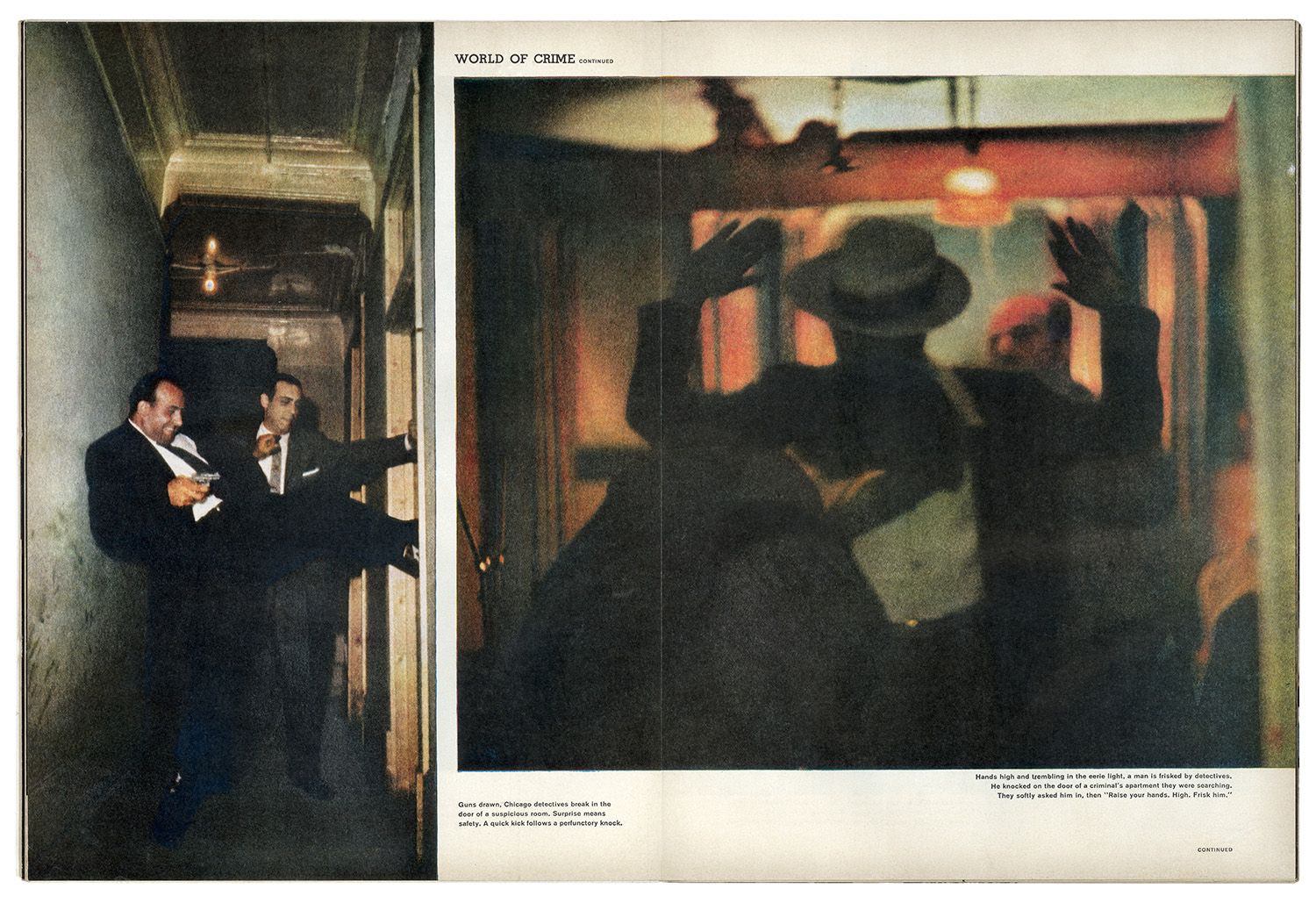

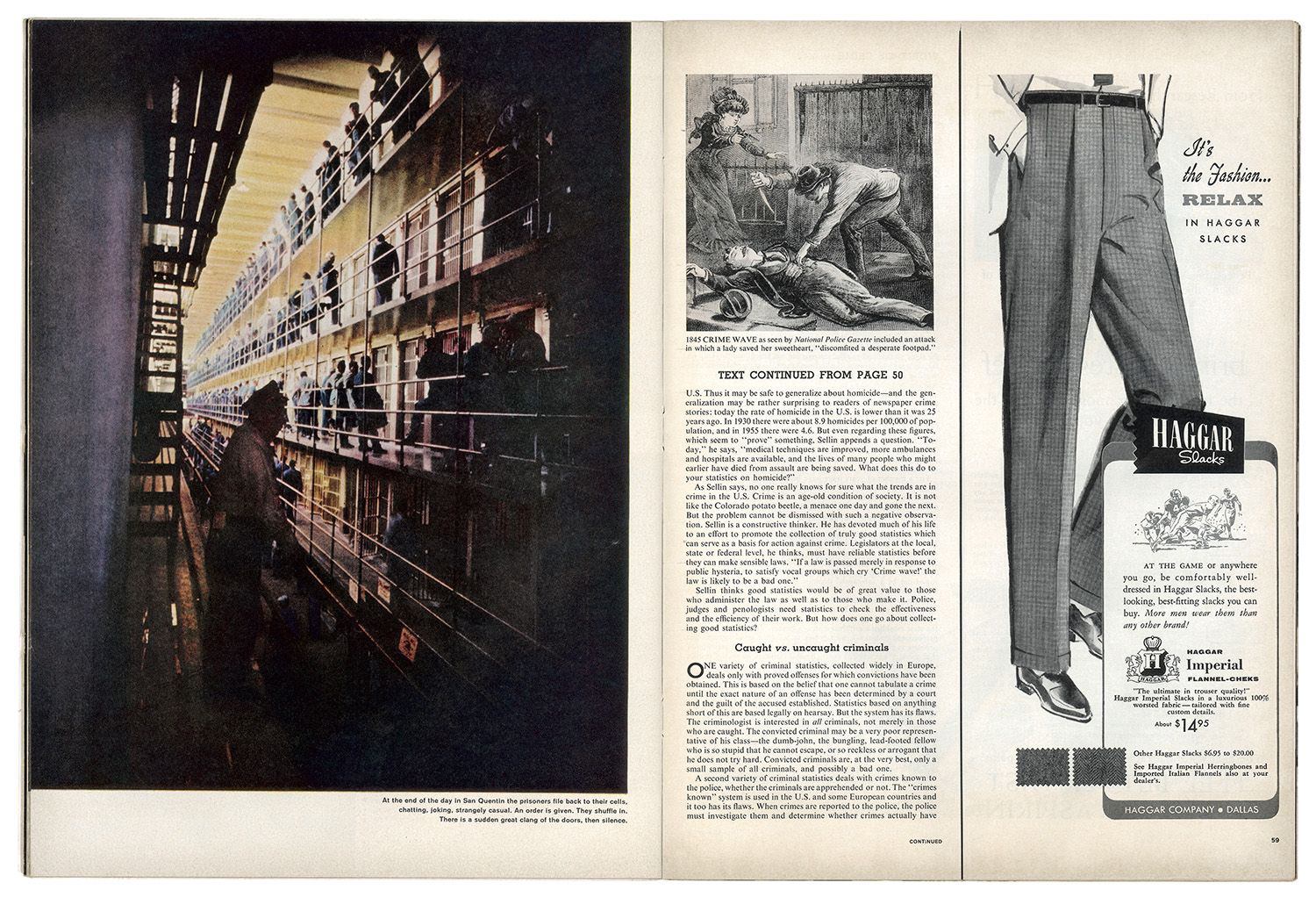

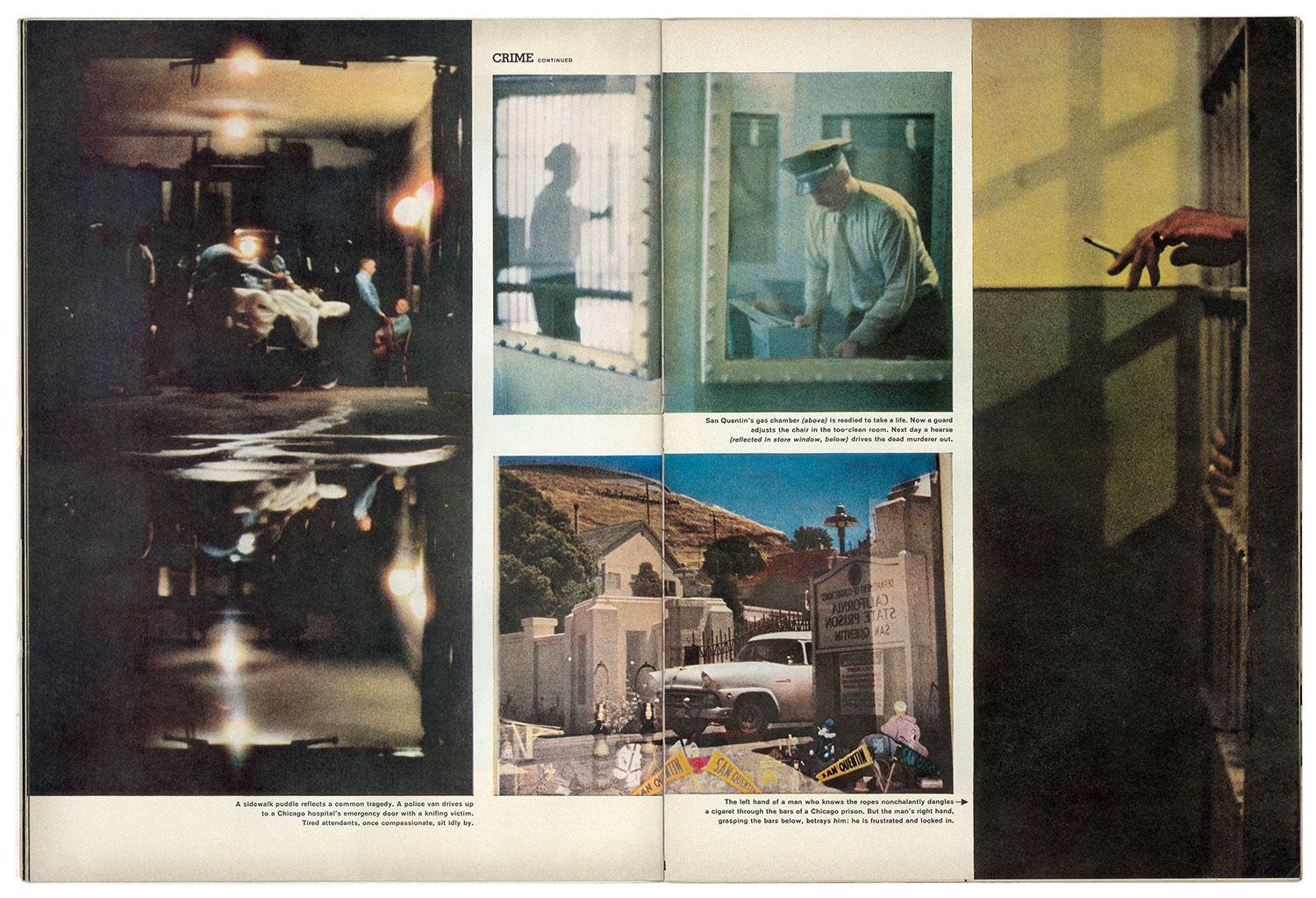

Unlike much of his prior work, the images made were in color. The resulting eight-page photo-essay The Atmosphere of Crime was noteworthy not only for its bold aesthetic sophistication but also for how it challenged stereotypes about criminality then pervasive in the mainstream media. They provided a richly hued, cinematic portrayal of a largely hidden world: that of violence, police work and incarceration, seen with empathy and candor.

Parks rejected clichés of delinquency, drug use, and corruption, opting for a more nuanced view that reflected the social and economic factors tied to criminal behavior and afforded a rare window into the working lives of those charged with preventing and prosecuting it. Transcending the romanticism of the gangster film, the suspense of the crime caper and the racially biased depictions of criminality then prevalent in American popular culture, Parks coaxed his camera to record reality so vividly and compellingly that it would allow Life’s readers to see the complexity of these chronically oversimplified situations. The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 includes an expansive selection of never-before-published photographs from Parks’ original reportage.

Edited by Steidl with text by Sarah Hermanson Meister. Foreword by Peter W. Kunhardt Jr., Glenn D. Lowry. Text by Nicole Fleetwood, Bryan Stevenson.

Co-published with The Gordon Parks Foundation and The Museum of Modern Art.

About the author

Gordon Parks, one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, was a humanitarian with a deep commitment to social justice. He left behind an exceptional body of work that documents American life and culture from the early 1940s into the 2000s, with a focus on race relations, poverty, civil rights, and urban life. Parks was also a distinguished composer, author, and filmmaker who interacted with many of the leading people of his era—from politicians and artists to athletes and other celebrities.

Born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912, Parks was drawn to photography as a young man when he saw images of migrant workers in a magazine. After buying a camera at a pawnshop, he taught himself how to use it. Despite his lack of professional training, he won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942; this led to a position with the photography section of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in Washington, D.C., and, later, the Office of War Information (OWI). Working for these agencies, which were then chronicling the nation’s social conditions, Parks quickly developed a personal style that would make him among the most celebrated photographers of his era. His extraordinary pictures allowed him to break the color line in professional photography while he created remarkably expressive images that consistently explored the social and economic impact of poverty, racism, and other forms of discrimination.

His most famous images, for instance, American Gothic (1942) and Emerging Man (1952), capture the essence of his activism and humanitarianism and have become iconic, defining their generation. They also helped rally support for the burgeoning civil rights movement, for which Parks himself was a tireless advocate as well as a documentarian.

Parks was a modern-day Renaissance man, whose creative practice extended beyond photography to encompass fiction and nonfiction writing, musical composition, filmmaking, and painting.

Parks spent much of the last three decades of his life evolving his style, and he continued working until his death in 2006.

He was recognized with more than fifty honorary doctorates, and among his numerous awards was the National Medal of Arts, which he received in 1988. Today, archives of his work reside at a number of institutions, including the Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, New York; the Gordon Parks Museum in Fort Scott, Kansas, and Wichita State University in Wichita; and the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Smithsonian Institution, all in Washington, D.C. Parks’ work is in the permanent collections of major museums, among them the Art Institute of Chicago; the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Cincinnati Art Museum; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the International Center of Photography, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, all in New York; the Minneapolis Institute of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Saint Louis Art Museum; the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.; and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

Hardcover: 168 pages

Publisher: Steidl/The Gordon Parks Foundation (June 25, 2020)

Language: English

Size: 9.8 x 11.5 inches

Weight: 1.7 pounds

ISBN-13: 978-3958296961

ISBN-10: 3958296963

Gordon Parks was born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912. An itinerant laborer, he worked as a brothel pianist and railcar porter, among other jobs, before buying a camera at a pawnshop, training himself and becoming a photographer. He evolved into a modern-day Renaissance man, finding success as a film director, writer and composer. The first African-American director to helm a major motion picture, he helped launch the blaxploitation genre with his film Shaft (1971). Parks died in 2006.