Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Proof of Color

Jacques Henri Lartigue, an undisputed figure in the world of photography, is best known for his black-and-white images capturing a society undergoing the industrial revolution.

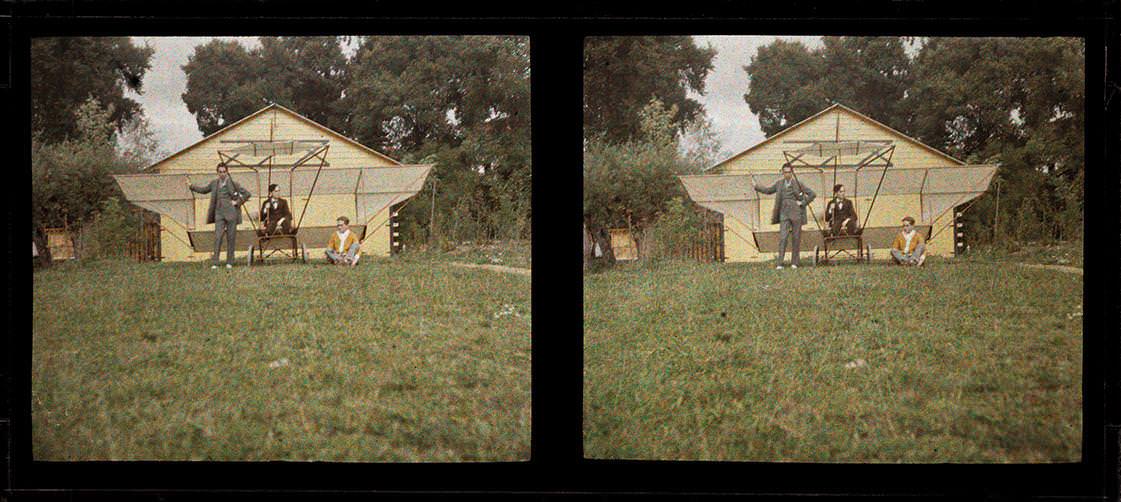

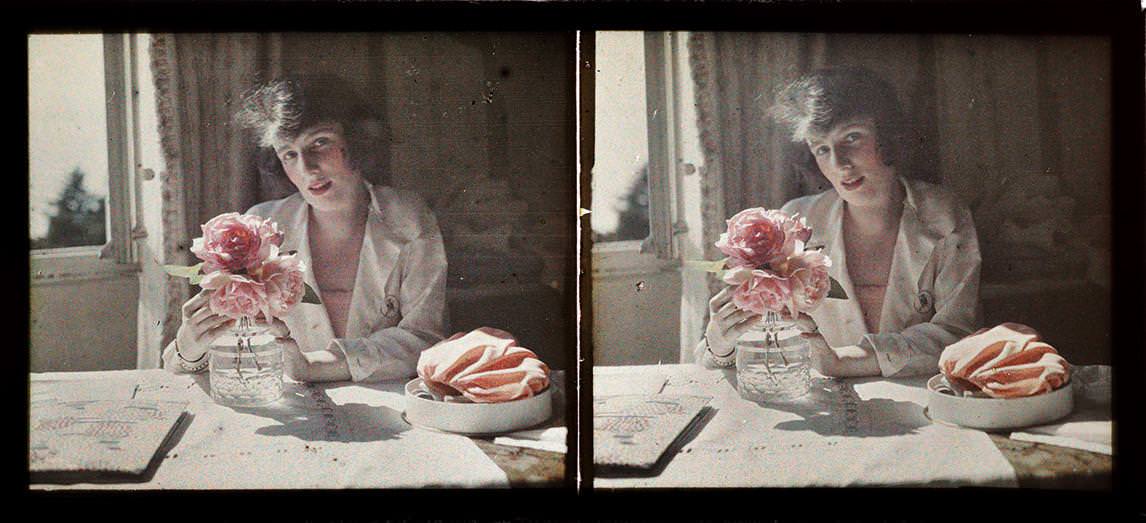

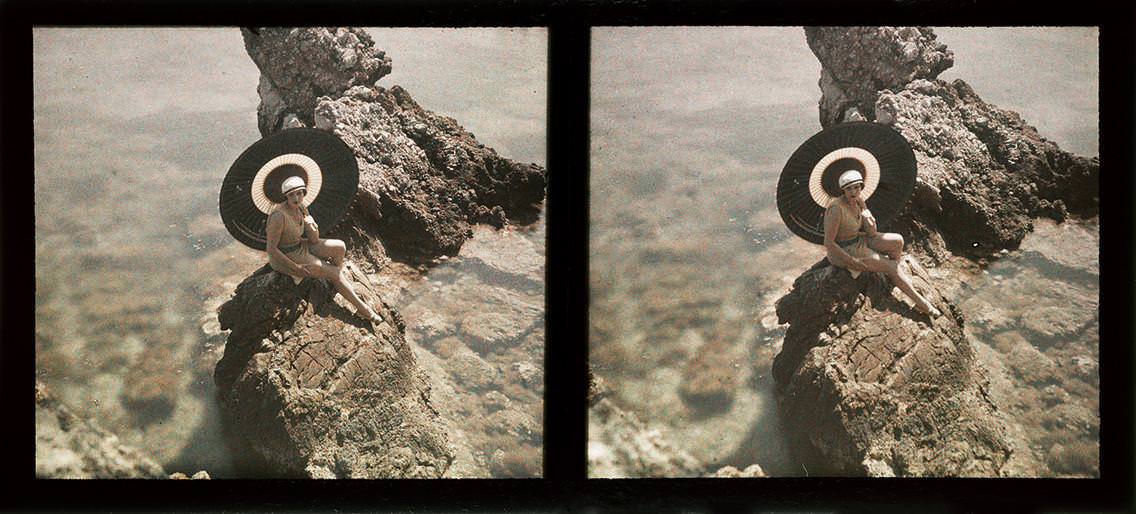

This book sheds light on a lesser-known aspect of Lartigue’s work: his fascination with stereoscopic Autochrome, one of the earliest color photography techniques recently introduced at the time. The 90 preserved plates, created between 1912 and 1928 and later in 1946, are presented here in full for the first time and in their original format.

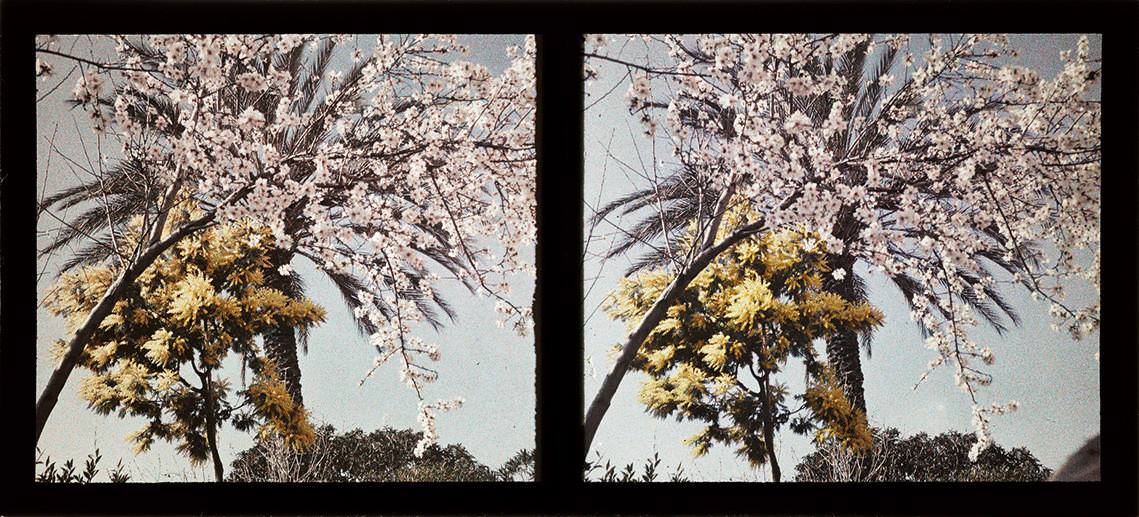

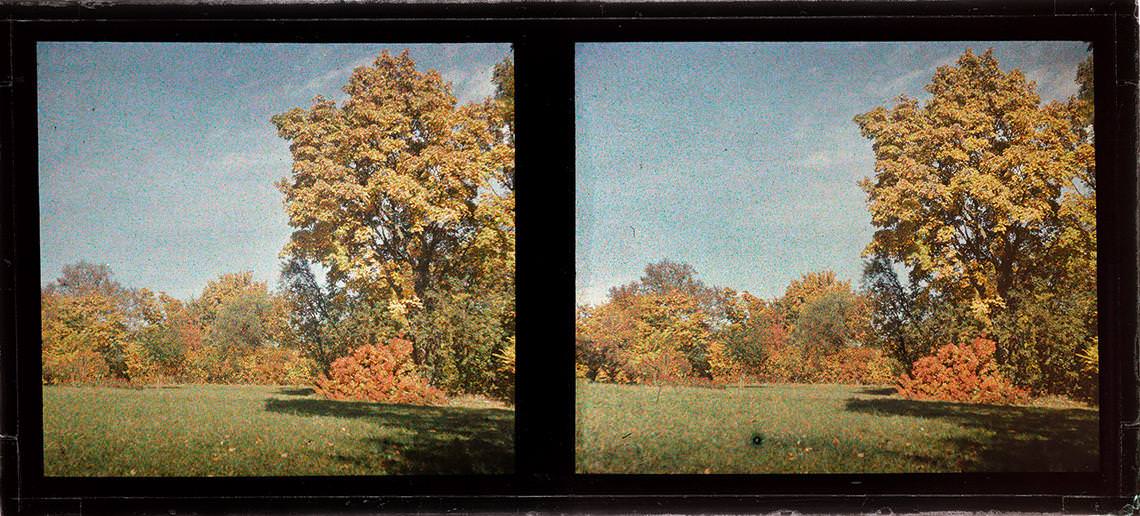

At the dawn of the 20th century, Jacques Henri Lartigue captured the thrill of speed and technological innovations, becoming fascinated with automobiles and the new possibilities that photography offered. Alongside this body of work, in 1912, he began exploring a radically different approach by using a technique that stood in stark contrast to his pursuit of motion: stereoscopic Autochrome on glass plates. This process required him to adopt a more deliberate and meticulous method, involving careful technical preparation and a long, precise exposure time to create his staged compositions. Instead of producing a print, the final result was a stereoscopic double image, which he projected onto a screen.

Lartigue focused on capturing scenes from the everyday lives of his close friends and family, from Sunday strolls to winter holidays. His frames are filled with vibrant colors, set within graphic compositions that combine sunlit landscapes, faces, flowers, and carefully selected clothing. During the brief period when he created these images (up until 1927), Lartigue produced 90 stereoscopic Autochromes, which are now being presented in their entirety and at full scale for the first time.

To fully grasp the significance of this series and its impact on the history of color photography—as well as its continued relevance—the collection is accompanied by critical commentary. Experts provide analysis and offer key reference points to deepen the understanding of Lartigue’s work. The texts are written by Marion Perceval, the director of the Jacques Henri Lartigue Donation, and art historian Kevin Moore, with full-color photographs included.

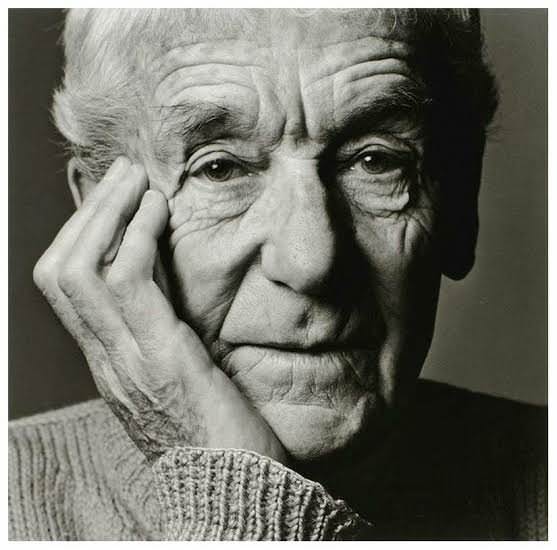

About the Author

Jacques Henri Lartigue remained relatively unknown as a photographer until 1963, when, at the age of 69, his work was showcased in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That same year, a series of his photos were published in Life magazine in an issue covering the death of John F. Kennedy, which introduced his work to a broader audience. To his surprise, he quickly became one of the most celebrated photographers of the 20th century.

Coming from a wealthy family, Lartigue and his brother were captivated by automobiles, aviation, and the popular sports of the time, all of which Jacques eagerly documented with his camera. As he grew older, he continued attending sporting events and capturing elite pastimes like skiing, skating, tennis, and golf. However, young Jacques was deeply aware of the fleeting nature of life and doubted that photography alone could preserve all the beauty and wonder around him. How could snapshots taken in mere seconds convey the depth of what he experienced?

Alongside his photography, Lartigue began keeping a diary, a practice he would maintain throughout his life. Determined not to sacrifice his freedom for a regular job, he lived modestly off his painting during the 1930s and 1940s. By the early 1950s, while still pursuing painting, his work as a photographer began to gain recognition.

In 1962, Lartigue and his third wife, Florette, traveled to New York, where they met Charles Rado, the founder of the Rapho photographic agency. After viewing Lartigue’s photographs, Rado introduced him to John Szarkowski, the new head of the photography department at MoMA. Szarkowski was so impressed that he organized Lartigue’s first-ever photography exhibition the following year.

A retrospective of Lartigue’s work was held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1975, the same year French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing asked him to take his official portrait. Lartigue continued to photograph, paint, and write until his death in Nice on September 12, 1986, at the age of 92. He left behind a legacy of more than 100,000 photographs, 7,000 pages of diary entries, and 1,500 paintings.