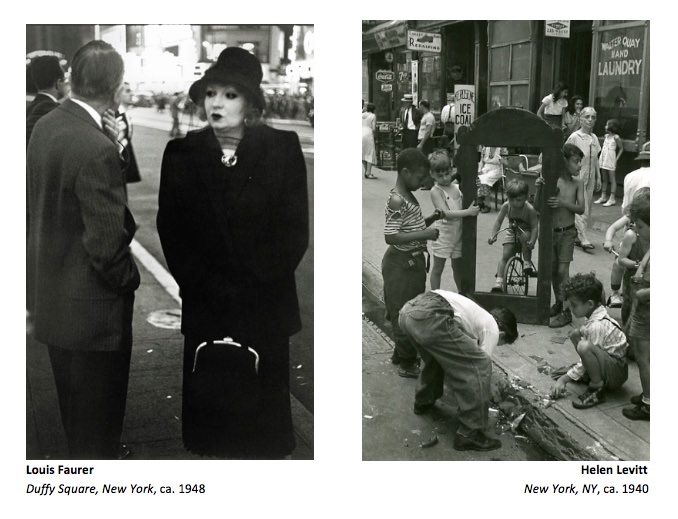

Louis Faurer / Helen Levitt: New York City, 1938-1988

Deborah Bell Photographs introduces an exhibition titled Louis Faurer / Helen Levitt: New York City, 1938–1988, featuring a collection of black-and-white and color images by the renowned American photographers Louis Faurer and Helen Levitt. Both artists deeply admired and held each other’s work in high esteem. Even though they matured during a time when photography was celebrated as a means for documenting social transformation, neither pursued the medium with the intent of issuing social critique.

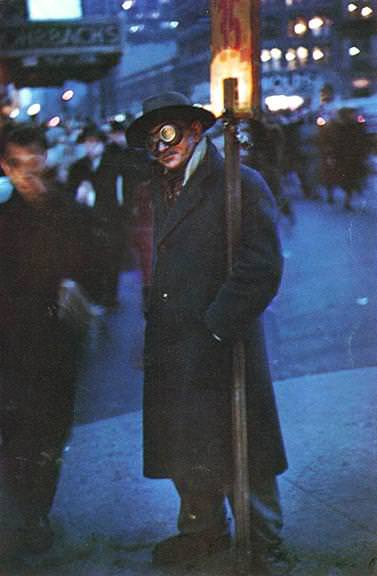

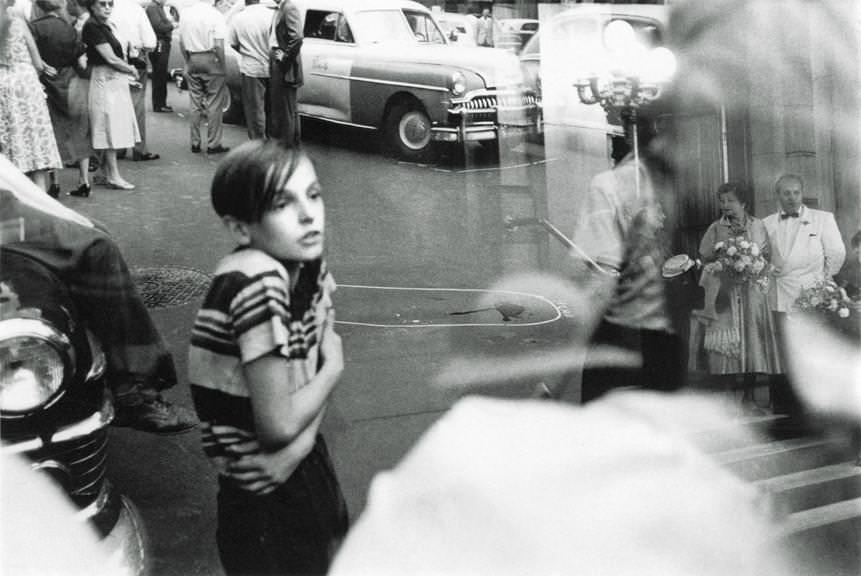

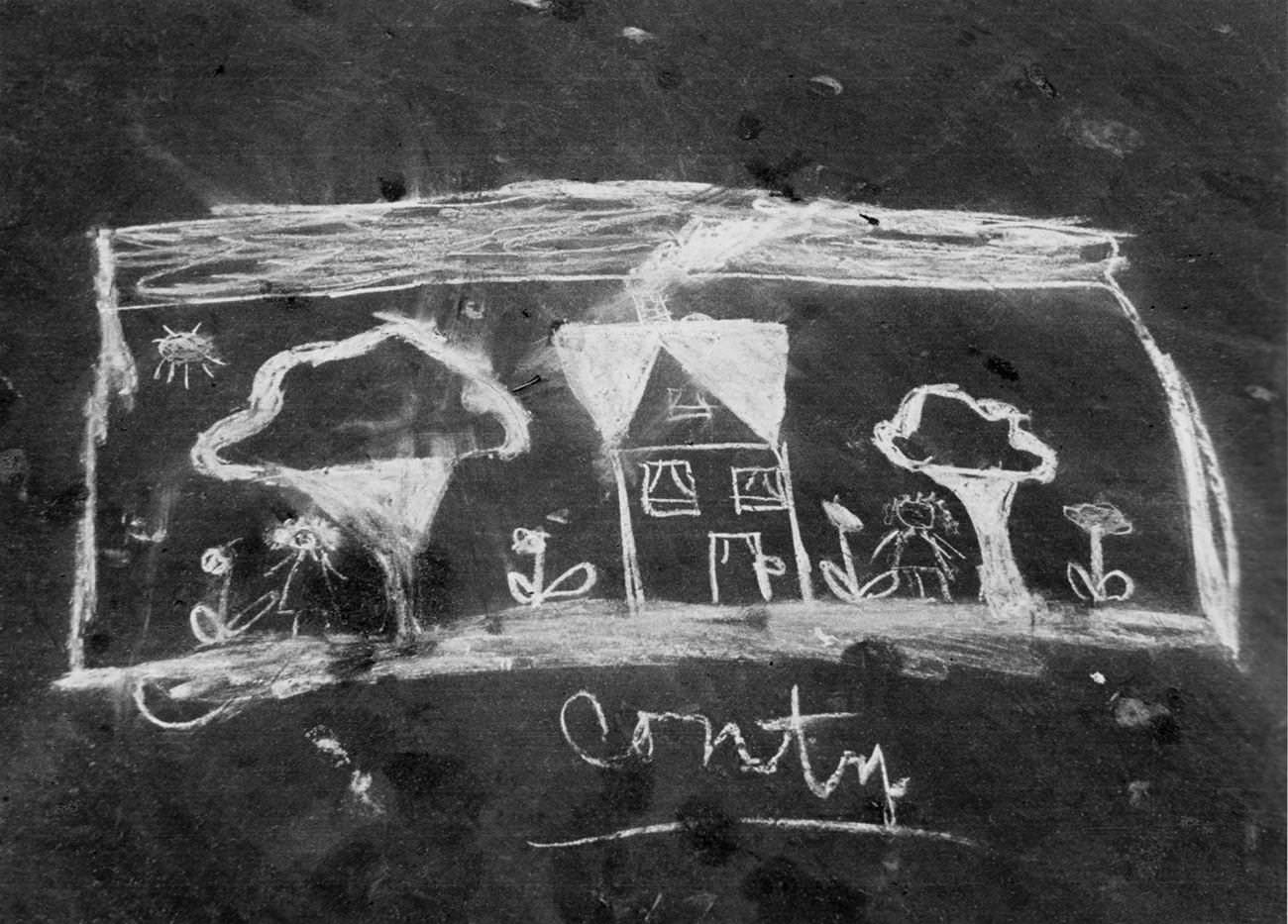

In Levitt’s playful captures of children’s mischievous exploits and their early chalk art, one finds an intimate chronicle of everyday encounters and exchanges among ordinary people. Conversely, Faurer’s sensitive yet unvarnished portrayals of nocturnal wanderers in Times Square, along with his layered, abstract depictions of urban landscapes, reveal his fascination with the magnetic energy of mid-century New York City.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York recognized the significance of both artists early in their careers. In 1940, Levitt’s work was showcased in the museum’s inaugural photography exhibition, under the guidance of Beaumont Newhall. This was followed by the 1943 show Helen Levitt: Photographs of Children, organized by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. Faurer’s photographs made their first appearance at MoMA in 1948 during Edward Steichen’s group exhibition In and Out of Focus, which also featured works by Levitt.

Born in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn (1913–2009), Helen Levitt discovered photography in 1931 while training under a portrait photographer, and by sixteen, she was determined to pursue it professionally. Relocating to Manhattan’s Yorkville in the early 1930s, she was inspired by friends Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans to invest in a 35mm camera and document New York’s streets by the late 1930s. Her early teaching stint in East Harlem under the Federal Art Project in 1937 paved the way for her work to appear in popular magazines like Fortune, U.S. Camera, Minicam, and PM. Levitt also earned acclaim for her film projects, beginning in 1947, and collaborated with James Agee and Janice Loeb on award-winning documentaries such as In the Street (1948 and 1952) and The Quiet One (1948). In 1964, she was awarded a Ford Foundation Fellowship for filmmaking. During the late 1940s, Agee and Levitt began working on a book of her photographs titled A Way of Seeing, featuring an essay by Agee, which was eventually published in 1965—ten years after his passing.

Curator Susan Kismaric observed in the catalogue for her 1981 exhibition American Children at MoMA that Levitt’s work was among the first in the nation to pioneer what would later be recognized as “street photography.” John Szarkowski, who led MoMA’s Department of Photographs from 1962 to 1991, described the captivating quality of Levitt’s early 1940s images: while her photographs depict ordinary scenes—children playing, middle-aged individuals running errands, and elderly people waiting—their power lies in revealing the grace, drama, humor, pathos, and unexpected beauty inherent in everyday life, as if the streets were a stage with its inhabitants performing an ongoing, unscripted play.

Louis Faurer, a Philadelphia native (1916–2001), graduated from South Philadelphia High School for Boys in 1934 and spent subsequent summers drawing caricatures along the Atlantic City Boardwalk. In 1937, he was introduced to photography by his high school friend, photographer Ben Somoroff, and soon began documenting life along Philadelphia’s Market Street. By 1946, Faurer was commuting between Philadelphia and New York, assisting photographer Ben Rose in a shared studio with fellow Philadelphian Arnold Newman. Walker Evans’ 1938 exhibition American Photographs at MoMA—and its accompanying catalogue—deeply influenced Faurer, who regarded it as a definitive guide for his work.

Anne Tucker, in her retrospective catalogue for Faurer’s exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, noted that while Faurer absorbed the empathetic approach of FSA photographers, he never aimed to use his work as a platform for social reform. Instead, he became known as a master of urban spaces—capturing the empty streets, overlapping signage, and surreal reflections that characterize city life. His work often focused on transitional zones, such as the gap between passing figures or the interplay between interior and exterior spaces in public transit or storefronts.

Faurer’s encounter with Robert Frank in 1947, shortly after Frank arrived from Switzerland at Harper’s Bazaar, marked the beginning of a lasting artistic bond rooted in a shared countercultural sensibility. Faurer was honing a 35mm aesthetic that hinted at the darker undercurrents of post-war America—a style that predated Frank’s fully developed approach. While contemporaries like Winogrand and Friedlander were also pioneering the 35mm style, Faurer’s work was distinctive for its intimate portrayal of strangers on city streets, blending the classic tradition of candid urban photography with a freshness previously unseen. His work also echoes the stylistic elements of film noir—marked by heavy use of shadows, unconventional compositions, and stark contrasts—as explained by curator Lisa Hostetler.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Faurer sustained his career by undertaking assignments for major publications such as LIFE and fashion magazines including Junior Bazaar, Harper’s Bazaar, Charm, Vogue, and Flair. At a time when dedicated photography galleries were scarce—Helen Gee’s Limelight Gallery being the notable exception—magazines served as the primary arena for photographic innovation and cultural discourse. Faurer once remarked that publication in these magazines was the true hallmark of an artist.

Reflecting on his career in 1979, Faurer recalled the formative years from 1946 to 1951, when daily shooting and the mesmerizing twilight in Times Square shaped his artistic journey. Represented in Edward Steichen’s In and Out of Focus exhibition, he later ventured to Europe in 1969 in search of new inspiration. Returning in the mid-seventies, he was struck by the transformed urban landscape of New York—a city that had become, in his words, his natural habitat. His renewed passion captured the essence of the “new New York,” and, as he put it, transformed the photographer into an artist.

Faurer’s late-1970s resurgence, fueled by the support of innovative photography galleries and collectors, was largely thanks to the legendary curator Walter Hopps and the influence of the painter and actress Susan Hoffmann (later known as Viva). In his 1979 essay CONCERNING LOUIS FAURER, Hopps recounted how, in 1976, he suddenly came to view contemporary American photography as belonging to Faurer. A serendipitous encounter with photographer William Eggleston and Viva led to a renewed public and professional interest in Faurer’s work. Hopps recalled recognizing images—originally seen in a 1950 issue of the lavish magazine Flair—that reshaped his perspective on photography. He praised New York City as the central stage for Faurer’s art, where his work reached unparalleled heights, comparable to the iconic imagery of Picasso’s Family of Saltimbanques. Despite remaining somewhat underrecognized in mainstream historical narratives, Faurer endures as a true master of his medium.

Louis Faurer / Helen Levitt: New York City, 1938-1988

Until April 19, 2025

Deborah Bell Photographs – New York

More info: